Raymond G. Alvine: A Pioneering Engineer

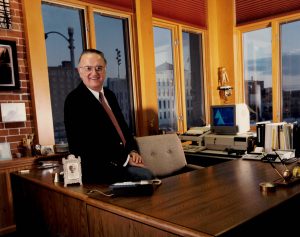

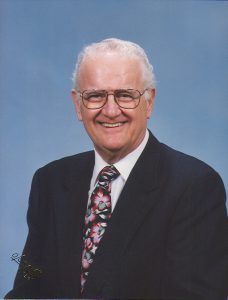

Raymond G. Alvine was a pioneering engineer in the eastern Nebraska and western Iowa region. Born in 1926, he earned his Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering from Iowa State University in 1949. In 1961, he founded Alvine and Associates (now Alvine Engineering), a one-man consulting firm that steadily grew under Ray’s leadership. He held a number of leadership positions within his community over the course of his career as a member of the Omaha, Nebraska Archdiocese Construction Review Board, Chairman of the Omaha Building Board of Review for nearly 20 years, and Chairman of the Advisory Board of the State Energy office from 1977–1979.

Raymond G. Alvine was a pioneering engineer in the eastern Nebraska and western Iowa region. Born in 1926, he earned his Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering from Iowa State University in 1949. In 1961, he founded Alvine and Associates (now Alvine Engineering), a one-man consulting firm that steadily grew under Ray’s leadership. He held a number of leadership positions within his community over the course of his career as a member of the Omaha, Nebraska Archdiocese Construction Review Board, Chairman of the Omaha Building Board of Review for nearly 20 years, and Chairman of the Advisory Board of the State Energy office from 1977–1979.

Lied Jungle at the Henry Doorly Zoo

His dedication did not go unnoticed and Ray was recognized with a variety of awards and honors throughout the years. He was named a Fellow in three professional societies: American Consulting Engineers Council/Nebraska (ACEC/N); Automated Procedures for Engineering Consultants (APEC); and American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). The Iowa Alpha Chapter of the Tau Beta Pi Association inducted him as Eminent Engineer and Ray was listed in “Who’s Who in the Midwest” and “Who’s Who in Engineering.” One of his most recognizable projects, the design of the Lied Jungle at Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo, was the recipient of the National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) 1993 National Honor Award.

Ray was a pioneer in many of the organizations that recognized him. He was a founding member and past president of the Nebraska Chapter of ACEC, which worked to organize the ethical standards and best-practices that guide the business-side of the state’s engineering firms. As a founding member of APEC, Ray helped focus the often-overwhelming potential of computers in the 1980s and ’90s, to better serve the architecture and engineering industry. He and his fellow members navigated the early machines, learning how to run engineering calculations, such as heating and cooling loads, which were all previously done by hand. As a life-long member of ASHRAE, Ray worked with his colleagues to usher in energy standards for the nation, channeling his passion for saving energy through efficient systems well before the widespread call for responsible energy management.

One of Ray’s favorite projects, a wood-burning boiler plant for Chadron State College in Chadron, Nebraska, is a perfect example of his trailblazing in energy efficiency. Completed in 1991, this facility was the first of its kind for any Nebraska institution, serving 18 buildings across the campus and reducing Chadron’s heating costs by nearly 50%. Ray was very proud of the finished project and used the experience in other projects, such as the wood-chip fueled fired boiler system at the National Arbor Day Foundation Lied Education and Conference Center in Nebraska City, Nebraska.

This is not the only time Ray looked for ways to respect the environment in engineering design. He also pioneered using groundwater for heat rejection to make chillers more efficient. Groundwater is plentiful in Nebraska and much cooler than water stored in a typical cooling tower, making it a more efficient alternative for rejecting building heat than a standard cooling tower system. For this reason, Ray developed some of the very first geothermal systems using wells as the source to cool a building’s chiller whenever possible. Originally, once it had been through the chiller, the water would simply be added to the storm sewer; however, as water conservation became more of a concern, the system needed to evolve and Ray found a solution.

Later projects included a supply well and a return well, where the water would go back into the ground (a few degrees warmer, but otherwise unchanged) after having been through the chiller. Some projects had areas (such as warehouses) that did not have air conditioning, but did have unit heaters. Whenever possible, Ray would route the well water through the chiller and then through the unit heaters before it made it to the return well. This did not provide workers with the benefit of full air-conditioning, but the difference of a few degrees during summer months was appreciated. Although few of these groundwater systems are still in use today, they were an important step during the 1980s in harmonizing engineering and the environment.

Ray was also passionate about mentoring and inspiring the next generation of engineers. He shared his knowledge around the world while serving as a visiting lecturer at seven universities in the People’s Republic of China as part of an ASHRAE delegation in the 1980s. In the office, Ray was a great mentor for his employees, finding time to meet with them whenever needed. His expectations for each person were clear and he gave everyone the opportunity to grow at their own pace. An engineering degree had significance, but did not mean that someone without a degree could not succeed at Alvine and Associates. Ray appreciated all his employees and their families; when people were hired at his company, he wanted it to be the job they had until they retired.

Ray was also passionate about mentoring and inspiring the next generation of engineers. He shared his knowledge around the world while serving as a visiting lecturer at seven universities in the People’s Republic of China as part of an ASHRAE delegation in the 1980s. In the office, Ray was a great mentor for his employees, finding time to meet with them whenever needed. His expectations for each person were clear and he gave everyone the opportunity to grow at their own pace. An engineering degree had significance, but did not mean that someone without a degree could not succeed at Alvine and Associates. Ray appreciated all his employees and their families; when people were hired at his company, he wanted it to be the job they had until they retired.

Ray was fair with everyone, practicing the same accountability and ethical business practices at his firm that he advocated for with ACEC. His early expectations laid the groundwork for Alvine Engineering’s modern business ideals. In fact, Ray and his small crew established many traditions that have since become a part of everyday life at the firm, including creative problem solving, delivery of the highest quality designs, and a culture of celebrating successes small and large (most often with doughnuts). In this way, as he did throughout his career, Ray Alvine led by example, pioneering engineering in the field, in the industry, and in the office.